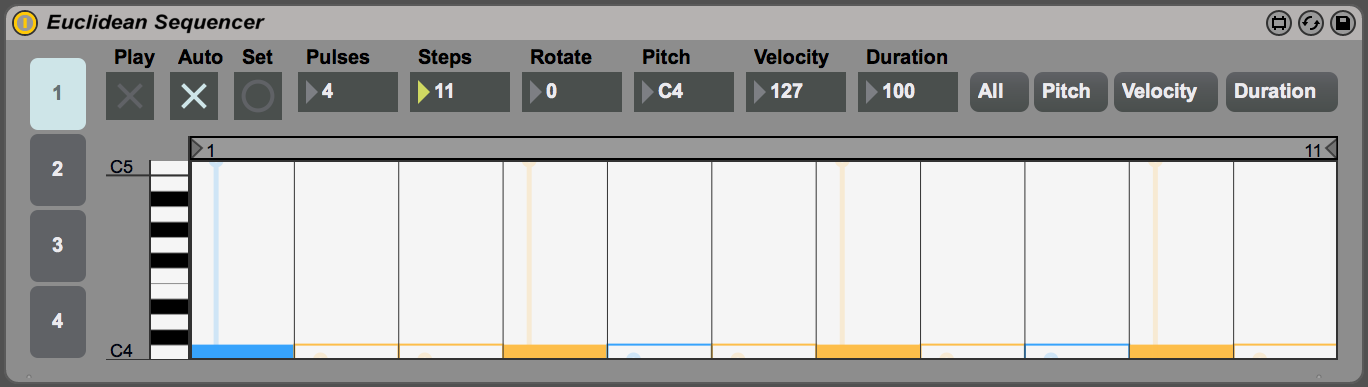

Euclidean Sequencer

I’ve built an Euclidean Sequencer1 for Ableton Live in Max for Live. I’ve been interested in Euclidean rhythm ever since I first heard about it because it looks like a good solution to some of the problems that come up when making music with a computer. Most of these problems revolve around what I call “the grid”.

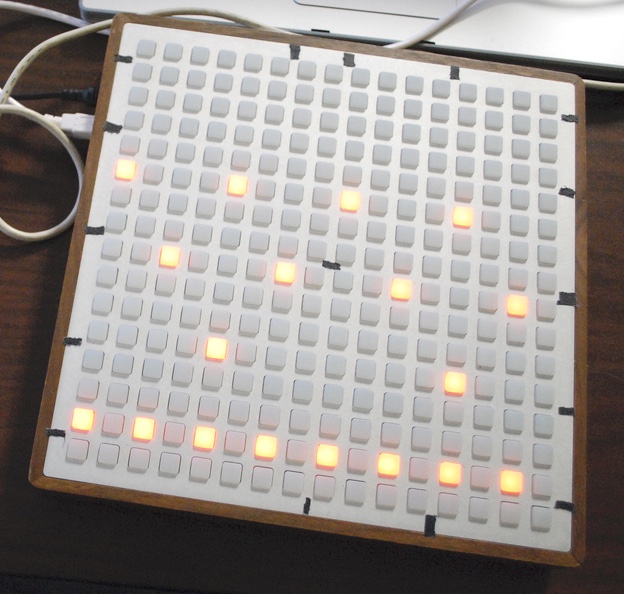

Monome 256 by soundcyst / CC BY-SA 2.0 / Cropped from original

This is a Monome2, it’s a 16 x 16 grid of LED buttons that can be mapped to control any aspect of an electronic composition. By far the most common thing they’re mapped to is sequencing notes in time (called “steps”). The 16 buttons across mean four steps per measure in 4/4 time3.

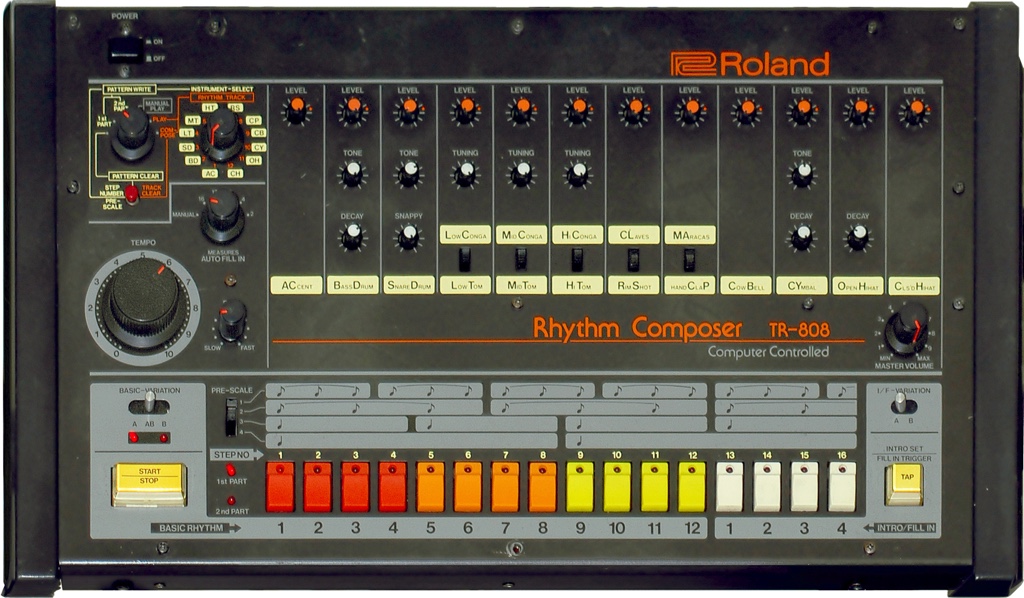

Roland TR-808 by Brandon Daniel / CC BY-SA 2.0

The Monome isn’t the originator of the 16 steps by any means, that goes back decades: The Roland TR-808 is a historic example of this layout. It’s an electronic music tradition that’s been passed down for generations.

The disadvantages of this design are obvious, the rhythmic possibilities of 16 steps were exhausted ages ago, but it’s the advantages that are more interesting. This small palette acts as a scaffolding for more adventurous ideas. It’s a familiar base that can lure listeners far outside of their comfort zone. It’s what allows DJs to blend songs together, the unsung benefit of DJ sets is just how much experimental music gets slipped in and actually enjoyed (by people who’d never otherwise find themselves staring face-to-face with a trout mask).

The grid has been so successful as a compositional tool that it permeates through all kinds of electronic instruments, to the degree that it can be an uphill battle to deviate from it. In many ways this is a good thing. Innovation happens when the common cases are effortless, freeing the musician to focus their effort on invention. The balancing act for new tools is how to facilitate the exploration of new ideas without interfering with existing workflows.

This is where Euclidean rhythm comes in. An Euclidean sequencer is basically polyrhythm generator, it takes two parameters: a number of notes and a number of steps; and it algorithmically positions the notes as equidistant as possible in the number of steps. For example, three notes and seven steps results in the pattern E(3,7) = [x . x . x . .]. It turns out that equidistant distribution is a key to creating rhythms that sound musical, an extraordinary number of traditional rhythms can be generated through this simple process, see the example rhythms section.

Polyrhythms are a great way to make rhythms sound fresh: Multiple repeating rhythms at different rates creates variation over time. And being difficult to work with, they’re under-explored. The grid in particular makes polyrhythms impossible in many situations, when the number steps that don’t match the 16 subdivisions, and difficult at best. The beauty of the Euclidean sequencer is that it simultaneously addresses all of these problems, while also working seamlessly with the benefits of grid.

Now I just have to make a tool to generatively manipulating the Euclidean sequencer’s parameters, and I can sit back and leave the music making to the machines entirely. I like making software more anyway. My Euclidean sequencer is on GitHub.

-

The repository has some nice examples of using Literate CoffeeScript to annotate the Euclidean algorithm. ↩︎

-

I love the Monome’s design because it distills the converging trend in electronic instrument design towards flexibility to its essence. Predictably, it’s been tremendously influential, a google image search for

grid midi controllerreveals seemingly endless Monome-inspired designs. ↩︎ -

The 16 steps are a great example of embracing constraints. ↩︎