The Five-Year Rule of Software Transitions

With software, I’m always trying to pick winners. I mainly care about the big apps1: the Photoshops, the Excels, the NLEs, DAWs, IDEs. Software people spend their whole day in, that can take a lifetime to learn, that a career can be built on. I’m interested in picking winners for these apps because they’re powerful and they’re hard to learn. So if I’m going to learn one, I want to be sure I pick the right one.

I say this upfront because it means when I’m talking about software transitions, I’m mainly talking about that kind of software, industry-leading creative software, and not, say, the next big social networking platform. It also means I’m mainly talking about desktop software, because this kind of software doesn’t have any traction on mobile.

I’ve been watching this kind of software for a long time, looking for trends, ideally based on any market share numbers I find. Over time I’ve noticed something interesting: Transitions in this kind of software almost always happen in the same way. In particular they happen quickly. And once they get going, they always seem to take roughly the same amount of time. I call this the “Five-Year Rule”. The rule is simple: Either a new piece of software will become the market leader in about five years, or it never will.

In this piece we’ll look at a five transitions closely. It’s notable that for the kind of software I’m interested in, these are the only transitions I’m aware of. Five isn’t very many for the ~35 year history of creative software. For each transition, I’ve listed the years I consider the transition to have taken place over. These vary in confidence level, in particular the farther I go back, the less data I tend to have, so choosing the years involves more guesswork.

The Transitions

- PageMaker to QuarkXPress: 1987–1993 (6 Years)

- QuarkXPress to InDesign: 1999–2005 (6 Years)

- Photoshop to Sketch: 2010–2015 (5 Years)

- Sketch to Figma: 2015–2020 (5 Years)

- The Rise of Visual Studio Code: 2015–2018 (3 Years)

Appendix Transitions

There’s an appendix section at the end where we look at a few more transitions that I also found interesting, but that don’t fit the mold of professional creative software that we’re looking at in the main transitions.

- The PC Revolution: 1989–1994 (5 Years)

- The Rise of Google Chrome: 2015–2018 (3 Years)

- Subversion to Git: 2005–2010 (5 Years)

Do Software Transitions Even Actually Happen?

The answer here is of course yes, many of us who follow software are fresh off the transition from Photoshop to Figma (for user-interface design). But things aren’t as straightforward with this transition as they seem. For example, today Photoshop is still likely more popular overall than Figma, with ~30 million Adobe Creative Cloud subscribers versus Figma’s ~4 million users. It’s hard to wrap your head around the supposed loser in a transition still being more popular than the winner.

I started thinking about this question, of whether software transitions ever really happen, when I noticed just how common it was for the most popular application in a category to still be the very first application that was ever released in that category, or, they became the market leader so long ago that they might as well have been. The Adobe Creative Cloud is a hotbed of the former: After Effects (1993, Mac), Illustrator (1987, Mac), Photoshop (1990, Mac), Premiere (1991, Mac), and Lightroom (2007, Mac/Windows) are all market leaders that were also first in their category. Microsoft Excel (1987, Mac) and Word (1983, Windows) are examples of the latter, applications that weren’t first but became market leaders so long ago they might as well be (PowerPoint [1987, Mac] is another example of the former).

Software of course has a reputation of being fast-moving, so I’m surprised at how little things have changed. The obvious explanation is that it’s hard to get people to switch from software that’s hard to learn (because they’ve already invested so much time and energy into learning the software they’re currently using). But I don’t find this explanation fully satisfying, since when transitions do happen, they happen very quickly, which seems to indicate that when something truly better comes along there isn’t any hesitancy about jumping ship.

Methodology

We’re going to look at some major transitions that happened in major creative software. The process of looking at these transitions is not scientific, “the Five-Year Rule” is really just a loose rule of thumb. It’s an observation about how transitions always seem to happen over a similar time frames, but everything about this evaluation process is fuzzy. For example, when do you mark the start date of a transition? I usually use the first release date of the software, but sometimes that doesn’t make sense. Take for example the current rise of DaVinci Resolve, Resolve was originally released in 2004, but for most of it’s lifetime it was a more specialized tool focused on color grading (and only had 100 users in 2009). Later Resolve was acquired by Blackmagc Design, who both reduced the price and added functionality to make it function as a standalone NLE (e.g., comparable other NLEs like Adobe Premiere and Final Cut Pro) with version 11 in 2014. In this case, 2014 makes more sense as the start date for the transition in NLE’s, and using that date it roughly follows the five-year rule:

The software had a user base of more than 2 million using the free version alone as of January 2019.[90] This is a comparable user base to Apple’s Final Cut Pro X, which also had 2 million users as of April 2017.

Then there’s the question of determining when a transition has occurred. To do this, I relied on market share numbers when available (looking for the date when an up-and-coming application overtakes the dominant player in popularity) usually from informal surveys conducted online. When no data is available, I resorted to anecdotal accounts I could find online. This is of course inherently flawed, but it seems like enough to make the case for a rough rule of thumb.

The Transitions

Transitions From the Design World

All the best software transitions are from the design world. This is because design as an industry consolidates around single applications for each category (for example, Figma for user-interface design, and InDesign for print design). I’m not sure why this is, but I think a contributing factor is that design is unique relative to most other creative fields, in that the designers output generally is not the final product, e.g., a design in Figma needs to actually be implemented separately in software. Whereas say, when editing a video, the exported video is the final product.

PageMaker to QuarkXPress

QuarkXPress goes from being it’s introduction in 1987 to 95% market share during the 1990s.

PageMaker 7.0 running on Mac OS 9

Aldus PageMaker was the first widely-used desktop publishing app. Three events happened in quick succession which ushered in the desktop publishing revolution:

- 1984: The debut of the Apple Macintosh

- 1985: The debut of the Apple LaserWriter

- 1985: The release of Aldus PageMaker

Soon after, QuarkXPress (1987, Mac) was released and began its ascent. There’s not much information available about this transition, but QuarkXPress version 5, released in 1990, appears to be the turning point. By 1994, when Adobe purchased Aldus, QuarkXPress was considered the dominate application by a wide margin.

The transition appears to roughly follow the five-year rule: QuarkXPress had 95% market share in the 1990s which makes it likely that by 1992 it had already surpassed PageMaker, the pattern that the five year rule predicts.

With that said, this isn’t a great example of a transition because it happened so early after the invention of desktop publishing, which means a PageMaker hadn’t really had enough time to become firmly entrenched yet. Transitions are the most interesting when they overcome the inertia an application has when it truly owns a category. This transition was included anyway because it helps set the stage for the next couple of transitions, which are also in the desktop publishing industry.

QuarkXPress to InDesign

QuarkXPress loses its dominate market position to Adobe InDesign over the course of about six years.

QuarkXPress

It’s hard to overstate how dominant QuarkXPress’s position was as the industry leader for desktop publishing software in the 1990s. For example, in 1998 Quark made an offer to buy Adobe.

But we don’t talk much about QuarkXPress today, it’s fall being so great that it’s drifted into irrelevance. I’ve always considered this the canonical software transition, because it went from being so dominate, to so rarely used. It happened long enough ago that it’s a story woven into the fabric of computing history.

How did InDesign beat QuarkXPress? It starts with our old friend PageMaker, and its parent company Aldus. Adobe purchased Aldus2 in 1995, with the intent of taking on QuarkXPress. InDesign was based on the source code to a successor to PageMaker Aldus had begun developing in-house and was first released in 1999:

[Adobe] continued to develop a new desktop publishing application. Aldus had begun developing a successor to PageMaker, which was code-named “Shuksan”. Later, Adobe code-named the project “K2”, and Adobe released InDesign 1.0 in 1999.

At the time, Quark had a reputation of having become complacent, making user hostile decisions just assuming their customers would go along with it. Dean Allen describes customers animosity towards Quark:

Pagemaker [sic], a crash-prone beast with a counterintuitive interface and slow as molasses in winter, was eventually bought by Adobe, whereupon everyone stopped using it and its unofficial name (‘Pagefucker’) took on common usage. This sent Quark flinging toward its destiny: to become a hostile monopoly spinning around in circles of pointless development, embracing dead-end technologies only to abandon customers once profitability proved unlikely, hobbling their own products with draconian antipiracy measures, signing unbendable licensing agreements in blood with newspaper chains, joining up with enemy Adobe to squish Quickdraw GX (one of many promising standards that actually showed a glimpse, at great development cost, of how sophisticated graphic design on computers could be before withering and dying once Quark said no thanks), and of course pissing off customers who paid a fortune for the privilege. And still it made horribly, horribly typeset pages.

Then there’s the bit where Quark bet against Mac OS X, Dave Girard for Ars Technica has an in-depth piece on the decline QuarkXPress that contains a choice quote from Quark CEO Fred Ebrahimi:

Quark repeatedly failed to make OS X-native versions of XPress—spanning versions 4.1, 5, and 6—but the company still asked for plenty of loot for the upgrades. With user frustration high with 2002’s Quark 5, CEO Fred Ebrahimi salted the wounds by taunting users to switch to Windows if they didn’t like it, saying, “The Macintosh platform is shrinking.” Ebrahimi suggested that anyone dissatisfied with Quark’s Mac commitment should “switch to something else.”

In 2003, after a few years of development of InDesign, John Gruber at Daring Fireball posted about InDesign vs. QuarkXPress:

Competition was restored when Adobe launched InDesign, which offers vastly superior typographic features than does QuarkXPress. But QuarkXPress still dominates the industry, even though InDesign:

- has been out for several years;

- is widely-hailed as a superior product;

- costs less;

- reads QuarkXPress documents; and

- comes from a company people actually like

Daring Fireball continued to post about QuarkXPress and InDesign, and reading the chronology of the subsequent posts traces a nice little history of InDesign overtaking QuarkXPress:

-

2003: “InDesign hasn’t taken more of the market away from Quark”

I’m not quite sure why this is, that “InDesign hasn’t taken more of the market away from Quark”. My best guess is that when Quark knocked off PageMaker, the industry was still nascent; but during the 90’s it matured and atrophied around Quark. InDesign may not be too little, but it might have been too late.

-

2005: “InDesign is clearly winning the horse race”:

Another interesting market share story is the relative position of Quark and InDesign. InDesign is clearly winning the horse race, with sales up 37%, while Quark book sales declined 35%.

-

2006: He doesn’t know “a single designer who hasn’t switched to InDesign”:

I personally don’t know a single designer who hasn’t switched to InDesign.

InDesign was released in 1999, so 1999–2006 is seven years, which is close enough for the accuracy we’re shooting for with the five-year rule. But that’s tracking until QuarkXPress has almost disappeared, whereas the five-year rule really tries to predict when the new player overtakes the original dominant player in popularity, which has happened earlier than that. Without any market share data to go on, we’ll just have to take a guess as to when that might have happened. For the purposes of this piece, I said six years, which is close enough accuracy for the five year rule.

InDesign

Photoshop to Sketch

Sketch becomes the most popular user-interface design tool, overtaking Photoshop over the course of about five years.

While the QuarkXPress and InDesign transitions feel like ancient history, Photoshop to Sketch still feels fresh. There’s so much mindshare around this transition, and even more so for the subsequent transition from Sketch to Figma, that they feel bound to be the new default case studies in software transitions.

Before getting into the history of Sketch itself, it’s important to quickly note the history of Fireworks, the dedicated design application that Adobe acquired as part of the the Macromedia acquisition in 2005. After the acquisition, development of Fireworks was quickly paused, citing too much overlap with Photoshop, it was later officially discontinued in 2013, but it had been considered long dead before that with designers.

Fireworks is important to mention because, while it never really set the world on fire, it had already demonstrated interest in a dedicated design app, and when it was discontinued a vacuum was left that Sketch was able to capitalize on. If you’re looking for where unexpected innovations will come from, look for areas of neglect.

Sketch was first release in 20103, but that’s not where its history begins, before Sketch, the company behind Sketch, Bohemian Coding, had a vector drawing app called DrawIt that would form its basis.

I worked as a user-interface designer at the time when Sketch was released, and at the time, Photoshop’s hold on the user-interface design market tenuous. User-interface designers only used a tiny portion of Photoshop’s features (mainly vector drawing tools and layer effects). The idea to break out those features into a separate, dedicated-design, app seemed was in the ether at the time (followed by adding some user-interface design specific features, like symbols). Adding fuel to the fire, around this time apps had begun leveraging the OS X Core Image and Core Graphics frameworks to make raster image editing apps replicating the functionality of Photoshop, like Pixelmator and Acorn. It seemed like only a matter of time until these same frameworks were leveraged to make a user-interface design app.

Sketch it made a splash with its initial release, but the inflection point was really the release of Sketch 3 in 20144, which included a key feature: Symbols. Symbols are re-usable components, an important feature when designing user-interfaces which usually require repeating the same element in different contexts with slight variations (e.g., picture the same button but with different text). By the Subtraction Design Tools Survey in 2015, Sketch had received the most votes as the designer’s tool of choice, beating out Photoshop by 5%.

How was Sketch able to disrupt a behemoth application like Photoshop? That had owned the design space for so long? On one hand, it was just focus: Photoshop is a photo editor first and foremost, using it for design was always a bit of a hack. But something else happened that paved the way for the rise of Sketch, and later Figma: Flat design.

Apple announced iOS 7 in 2013, radically changing the user-interface design of iOS. Before flat design, Apple had been pushing a skeumorphic style simulating real-world objects using rich textures and whimsical animations. Photoshop, which combined rich bitmap editing features with vector editing tools, was a much better fit for the skeumorphic style than the austere flat design.

Wikipedia’s iOS 6 and iOS 7 screenshots side-by-side

Review for iPad, an app I designed during the skeumorphic era

I think it’s underappreciated just how bizarre the change from skeumorphic to flat design was to the design tool market. For the capabilities that a software package requires to serve a market to suddenly reduce so drastically was unprecedented. It’s like if 3D modeling software suddenly didn’t care about realistic textures and lighting. Of course that would open up the market to being disrupted. The priorities of the software have changed dramatically, making room for new approaches. An opportunity that more nimble startups would be best positioned to capitalize on while the larger software packages, who already have a lot of customers depending on their existing feature set, would be slower to adapt.

To top it all off, flat design also facilitated a new workflow for designers that Sketch was also able to capitalize on: Photoshop had always been used to actually export image assets that were then reassembled in code to create the design. Sketch (and later Figma) never really had to work this way, since flat design is mainly comprised of text, lines, and gradients, rather than textures, which can easily be created in code themselves, so don’t need to be exported5.

I’d argue that not needing to export assets is a larger change than it might seem like, because it changes which category user-interface design software fits into. For example, all of the other major applications in the Adobe Creative suite, like Premiere, Photoshop, and Illustrator, the final asset (the photo, the movie, the artwork) is actually exported from the application. In that way, Premiere, Photoshop, and Illustrator fit into a one category of sofware: Applications for making digital content. Figma and Sketch (outside of the occasional SVG export) are mainly software for communicating a design. In that way, they’re closer to presentation software like Keynote and PowerPoint, than they are to rest of the Adobe suite. Presentation software, like Sketch and Figma, are used to communicate ideas, not build the actual artifacts used to create digital content.

You can blame Adobe for missing the boat on user-interface design deserving their own tool, instead of shoehorning a photo editor for that purpose—I’d love to have been a fly on the wall in the decision to kill Fireworks for example—but it feels harder to fault them for not realizing that this new dedicated design tool would also be closer to Google Slides than to the other software in Adobe’s Creative Suite that’s their bread and butter like Premiere, Photoshop, and Illustrator.

Sketch to Figma

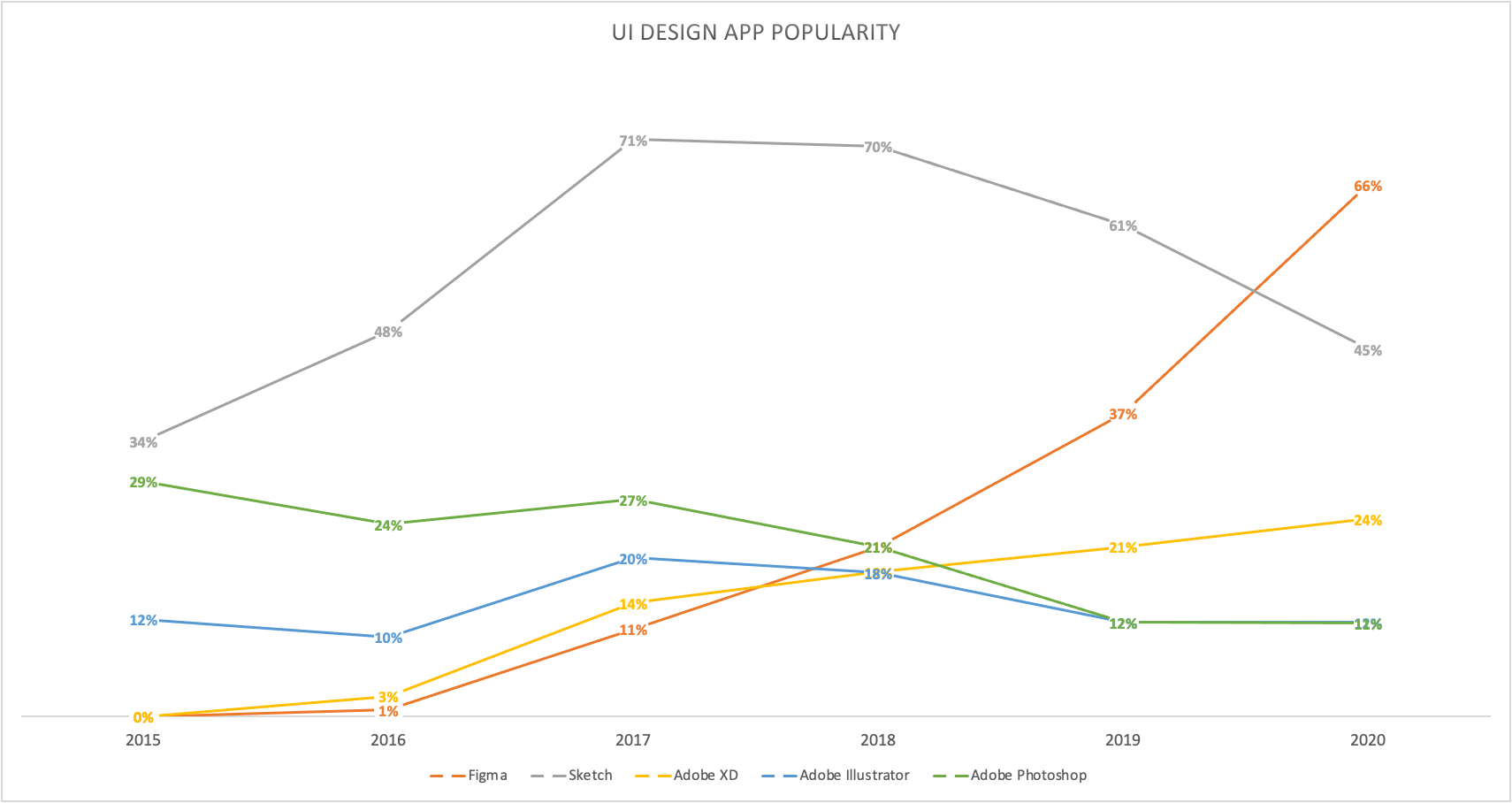

UI design tool popularity from the Subtraction Design Tools Survey (2015) and UX Tools (2016-2020)

This graph illustrates not just that Figma overtook Sketch over about five years (2015–2020), but also Sketch’s own five-year ascent to overtake Photoshop (since Sketch was released in 2010 and it starts out ahead in 2015).

Dylan Field and Evan Wallace started working on Figma in 2012, and it was initially released in 2016. Figma runs entirely in the browser, it has a 2D WebGL rendering engine, built in C++ and compiled to WebAssumbly, with user-interface elements implemented in React. This stack really excited a lot of people, because, before Figma there had never been a successful creative app that was a web app. After seeing The Matrix, film director Darren Aronofsky’s asked “what kind of science fiction movie can people make now?”. Similarly, after the success of Figma, startup founders have been asking “what kinds of software can be made as web apps now?” So far the answer has been “not many”, I’m not aware of a single other startup that has fulfilled this promise6.

As was mentioned at the end of the PageMaker to QuarkXPress section, it’s actually quite common for transitions to happen soon after the introduction of a new software category, before an application has time to become firmly entrenched in actually owning a category. For example, Microsoft Word came four years after WordPerfect, and Microsoft Excel came eight years after VisiCalc. There’s a “primordial ooze” phase right after a new category emerges where lack of product maturity means it’s relatively easy for new players to enter a category until a dominant player emerges. Sure, it’s still interesting to look at the factors that determined which application becomes successful through that process, but what’s more interesting is when an application has had time to become entrenched and then gets supplanted. In this case, the entrenched application was Photoshop, and the application responsible for supplanting it was Sketch, not Figma.

In the section on Photoshop to Sketch, we discussed an underappreciated factor in Sketch’s, and by extension, Figma’s, success: That flat design shifted the category of design software from professional creative software to something more akin to an office suite app (presentation software, like Google Slides, being the closest sibling). By the time work was starting on Figma in 2012, office suite software had already been long available and popular on the web, Google Docs was first released in 2006. This explains why no other application has been able to follow in Figma’s footsteps by bringing creative software to the web: Figma didn’t blaze a trail for other professional creative software to move to the web, instead Sketch blazed a trail for design software to become office suite software, a category that was already successful on the web.

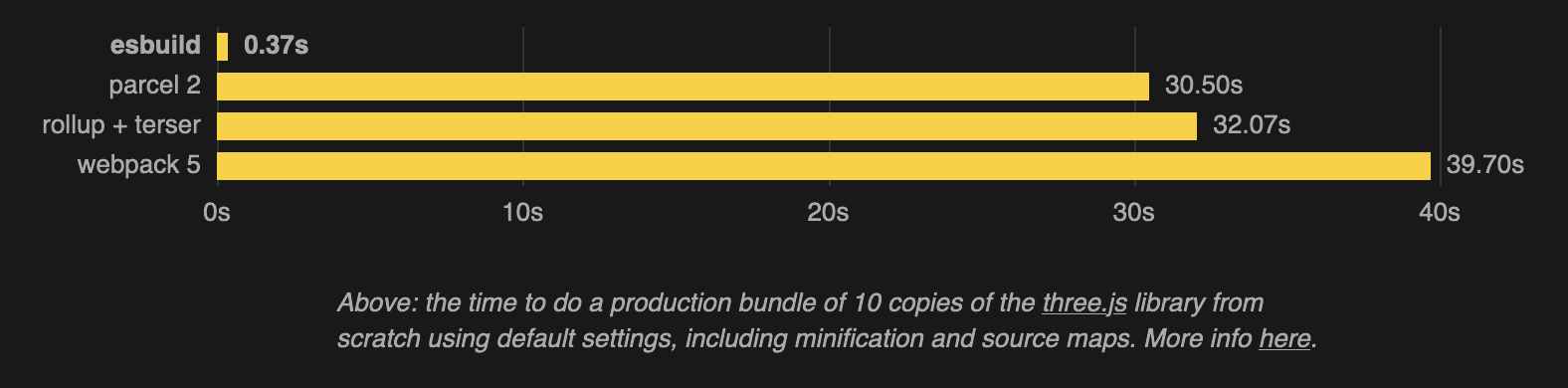

Another factor that’s rarely mentioned in Figma’s success is that co-founder and former CTO Evan Wallace appears to me to be a once in a generation programmer, deserving to be on a short list with the likes of Ken Thompson, Linus Torvalds, and John Carmack. Figma itself is evidence of Wallace’s skill, especially since no other company seems to be able to make another web app that feels as nice. It’s rare for a technical implementation to act as a moat, but that appears to be what has happened with Figma. For evidence of how widespread the architecture Wallace pioneered for Figma is expanding, Google Docs is switching to canvas-based rendering. I’m also struck by the startling beauty of some of his early work that predates Figma, like this gorgeous WebGL water simulation presumably done while Wallace was studying computer graphics at Brown University. Then there’s esbuild, a JavaScript bundler like webpack, with amazing performance. The homepage for esbuild sports this graph:

There’s a point at which the magnitude of the performance improvements starts to show contempt for your competitors, and esbuild crosses that line. Wallace left Figma at the end of 2021, less than a year before Adobe’s acquisition of Figma was announced in 2022.

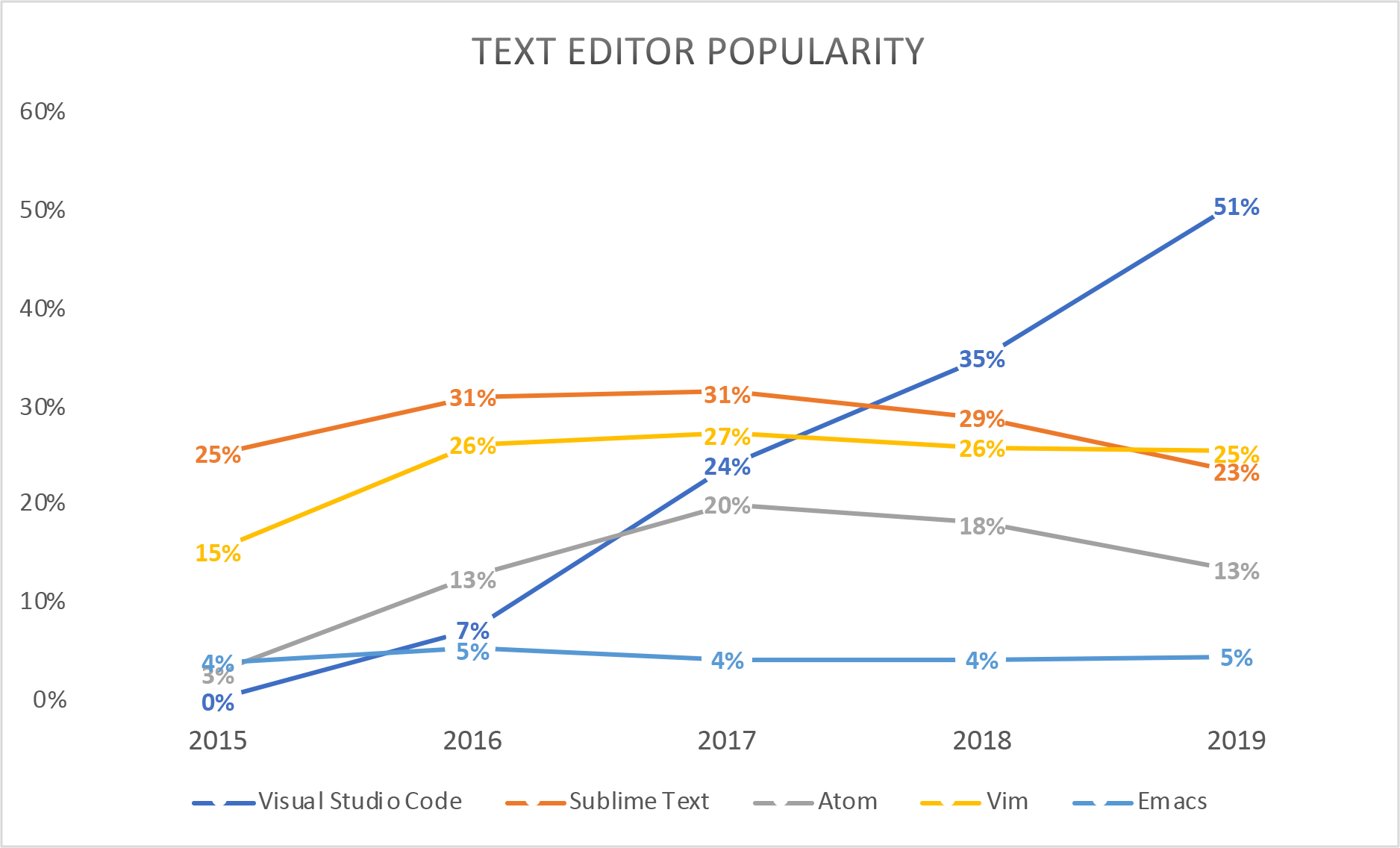

The Rise of Visual Studio Code

Visual Studio Code, first released in 2015, becomes the most popular text editor by 2018, over the course of just three years.

I’ve already written about the rise of Visual Studio Code. In some ways the rise of VS Code is similar to Figma, in that another, earlier, trailblazer first disrupted the market, before they came in and really took over. In Figma’s case it was Sketch, and in VS Code’s case it’s Atom, released a year before VS Code in 2014. Atom illustrated that there was a market for an open-source web-based text editor built around extensions7. VS Code took that formula and solved the main problem that held it back: Performance. Atom was known as being slow, and VS Code has a reputation of being snappy in comparison.

Conclusion

I looked at six examples of software transitions of big creative apps, starting with tracing the history of print design, then transitions from the user-interface design world, and finally the rise of Visual Studio Code. In this, imperfect, but hopefully still useful, analysis, all of those transitions took between three and six years with an average (and median) of five years.

When I started out writing this piece, there were a few things I wanted to illustrate. The first was that transitions even happen at all with big creative software that’s firmly entrenched in an industry. There’s a perception that most of the preference for one application over another just comes down to path dependence. And there’s a lot to that argument, these kinds of applications8 often have whole asset pipelines built around them9. But if we can illustrate that transitions do happen, then perhaps it’s less about inertia and more about the relative merits of different software packages? In the end, I found evidence of this lukewarm at best. Out of the five transitions I looked at: two of them (PageMaker to QuarkXPress and Sketch to Figma) are “primordial ooze” transitions, i.e., transitions that happened early enough after the creation of a new software category that there wasn’t enough time for path dependence to become a factor. That leaves just three transitions: QuarkXPress to InDesign, Photoshop to Sketch, and the Rise of Visual Studio Code. That’s not very many for ~35 year old industry10.

Another reason I wrote this piece is to illustrate where transitions are unlikely to happen. A lot of software just hums along with lower usage numbers, and yet I often see people commenting on how it’s on a path to disrupt an industry. But I don’t think an application humming along at lower usage numbers has ever ended up disrupting an industry. That doesn’t mean it can’ be a great business, but Adobe (the company that comes up again and again in this piece) has ~26,000 employees. The question is what scale the software will operate at. Ableton has ~350 employees and Maxon has ~300, anecdotally it seems like a lot of software categories can operate at 100> employees, but 100+ really requires owning a market of some kind.

Overall my conclusion is that what accounts for the rarity of transitions is that for a transition to happen, one of two pre-conditions need to happen that are completely outside of the control of the new piece of software: One is that the existing market leader has to make a major mistake. QuarkXPress betting against OS X for the print industry, and Adobe killing there design-focused tool Fireworks, are examples of this. The second is that a fundamental shift to the industry can happen, the rise of flat design coinciding with the ascent of Sketch is an example of this. Similarly, with the rise of web-based software on the list (VS Code and Figma), a technical groundwork had to be in place before these could become viable. For example, for Figma to create their web-based performant graphics engine, WebGL (initial release in 2011) and asm.js (initial release in 2013) both had to be in place.

In the end, just building a great software product is not enough to lead to a transition, you also need the incumbent market leader to make a mistake, or market conditions to fundamentally change (often due to new technology breakthroughs), and preferably both.

Appendix

In the appendix I’ll look at a few more interesting transitions that don’t fit in the narrow category of professional creative software.

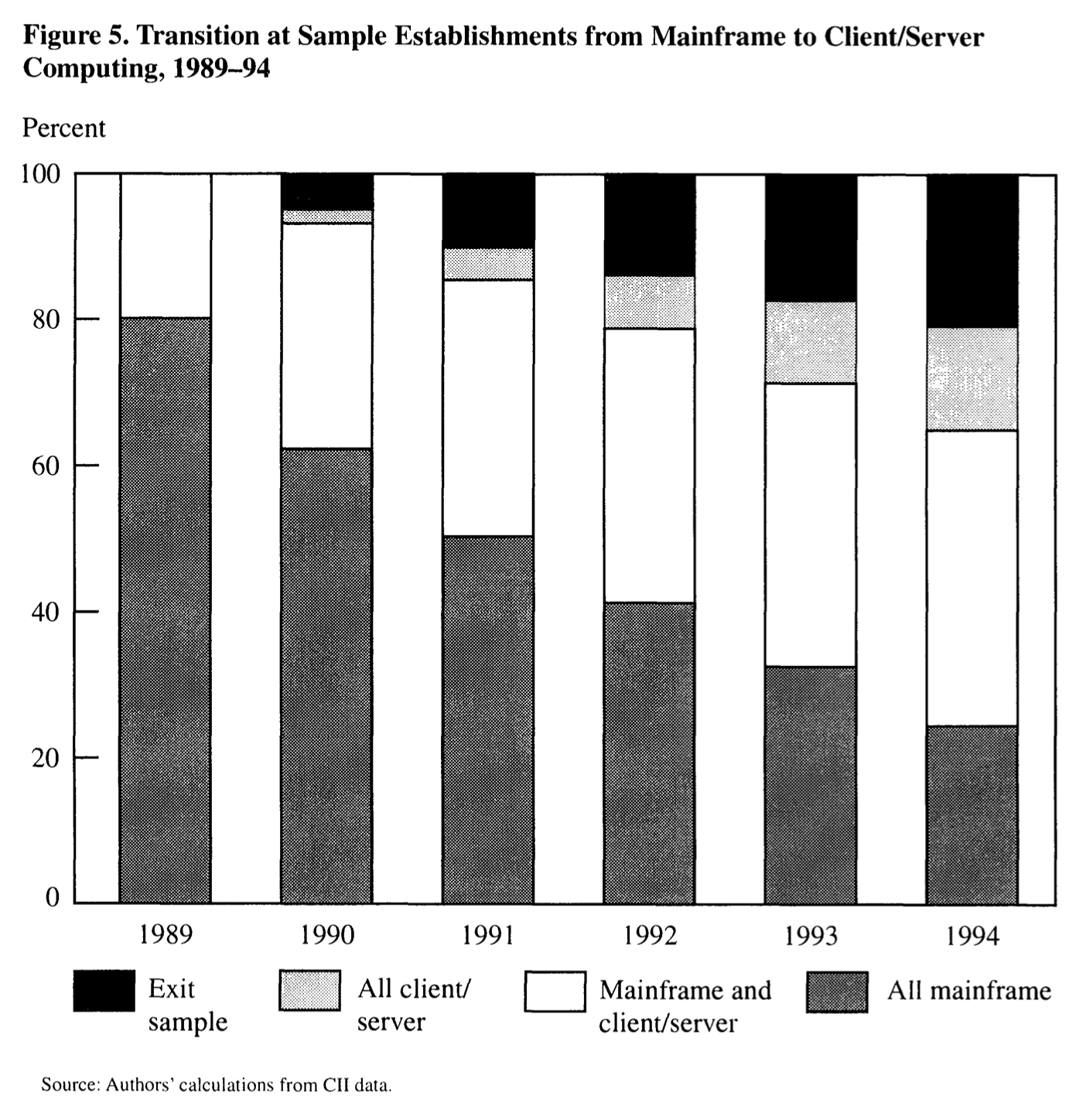

The PC Revolution

Client-Server Architecture usage at businesses goes from 20% to over 50% in four years from 1989 to 1992.

The PC revolution had a several phases. There’s the introduction mass market computers like the Apple II, but that was an introduction not a transition (i.e., people buying a computer for the first time, not switching from one kind of computer to another), so it’s less relevant to this piece. What’s more relevant is the transition from predominantly centralized computing (e.g., a mainframes or minicomputers), to the client-server model, where the client and server are both commodity PCs (under the centralized computing model, terminals and mainframes are radically different architectures).

This transition is of course distant history. I’m mainly relying on one source: A paper titled Technical Progress and Co-invention in Computing and in the Uses of Computers by Timothy Bresnahan (Stanford University) and Shane Greenstein (University of Illinois), published in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity in 1996.

The focus of Bresnahan and Greenstein’s paper isn’t about why companies were transitioning from mainframes to client-server, it takes the stance of assuming the switch is inevitable, and is more concerned about what might slow it down, given the advantages were obvious. Here’s how they described the advantages of the client-server model:

Client/server computing emerged as a viable solution to the problem by promising to combine the power of traditional mainframe systems with the ease of use of personal computers (PCs). A network could permit the functions of a business system to be divided between powerful “servers” and easy to use “clients.” By the late 1980s the promise of C/S was articulated and demonstrated in prototypes, and the competitive impact was quick and powerful. Firms selling traditional large-scale computer systems saw dramatic falls in sales, profits, and market value.

As to what slowed down the switch, Bresnahan and Greenstein mainly attribute this to the additional cost of “co-invention”: The additional work required by businesses to adapt the new computing model to their needs (distinguished from “invention”, because this work is done by the businesses themselves):

Despite the speed and ambition of this technical progress, C/S did not become strictly better than mainframes. Instead, by the mid-1990s, each platform had distinct advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, pre-existing data and programs for large applications were (necessarily) on host-based systems. If newly developed applications were simply improvements to the old, then there would be cost advantages to continuity. If new applications also needed to interact with the old programs or data, even greater advantage would arise. Finally, even with many technical problems solved, C/S still called for co-invention, which was potentially costly and time consuming, especially for complex applications. Hence, some users were going to switch cautiously, if at all.

Figuring out how long the transition from mainframes to the client-server model took is more difficult than with software, because there isn’t a clear date to mark the start of the transition. With software, we can use the first release date of the software, but with something like the client-server model, which had many moving parts evolving together to eventually create a compelling package, there isn’t an obvious start date. Bresnahan and Greenstein choose 1989 as the start date, because in their words, “before 1989 workstations and personal computers could no more replace mainframes than could the people of Lilliput wrestle Gulliver to the ground.”

The sample of companies and their distribution of mainframe versus client-server over time.

Client-server starts out at about 20% in 198911, and the sum mixed of mainframe and client-server businesses and all client-server businesses surpasses all mainframe in 1992, so that’s four years12.

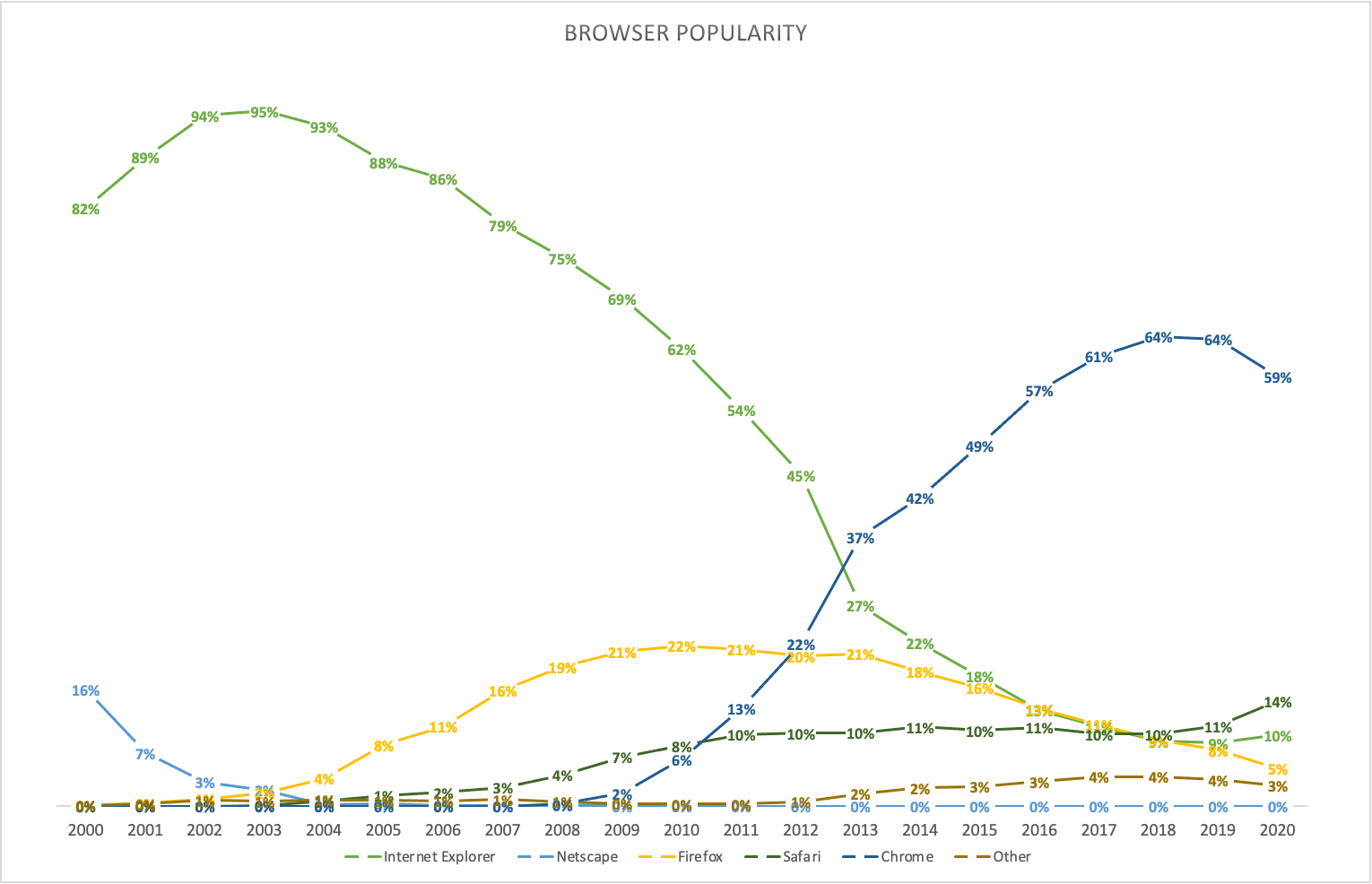

The Rise of Google Chrome

Google Chrome is introduced in 2008 and becomes the most popular browser five years later in 2013.

One of the most popular transitions to discuss is browser market share because it’s so impactful. The browser popularity has special significance because the browser is an application that runs other applications, and therefore determines a lot about the fate of the web apps that run in the browser.

Additionally, through the very nature of the browser, it’s very easy to collect market share data. The main use of the browser is to access arbitrary remote servers, so all you need to do collect market share numbers is for some of those servers to record which browser is being used to access the site. A number of different sites have done that over the years.

Browser usage data aggregated from the *Usage share of web browsers* Wikipedia page13 which includes data from several different sources.

Firefox (released in 2002) once looked like it was on a trajectory to become the market leader. If it had, it would have been the slowest transitions in this piece. But it didn’t, instead it plateaued almost immediately when Google Chrome was released in 2008. An interesting question is if Chrome hadn’t come along, would Firefox eventually have become the market leader? I don’t really have an answer to that question, but the five-year rule would say no, that the transition was happening too slowly, a more likely outcome is that the market opportunity (in this case created by the stagnation of Internet Explorer) would be capitalized on by a more aggressive player that completes the transition over the course of roughly five years, which is exactly what happened.

Chrome’s rise is a textbook example of the five year rule, released in 200814 and becoming most popular browser in 2013. Google themselves have a wonderful comic with words from the Chrome team and illustrations by Scott McCloud (of Understanding Comics fame). The overall message is that the browser was originally designed for sharing documents, but that the web had moved towards serving applications, instead of documents, so Chrome is a browser designed from the ground up to serve applications. The features they emphasize are operating-system-style process isolation (an innovation that is now standard across all browsers), a new JavaScript VM (V8) built from the ground-up for web apps (e.g., introducing JIT compilation, a user-interface focused around tabs (e.g., the Omnibox), and incognito mode.

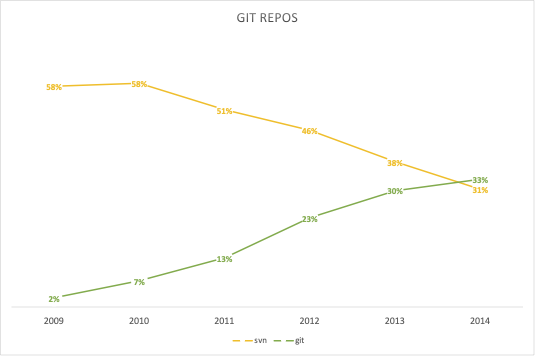

Subversion to Git

git is introduced in 2005 and the total number of repositories using git overtakes Apache Subversion nine years later in 2014. But I’d argue more developers were using git for their work in five years, by 2010.

The total number of repositories using Subversion vs. git. The data was collected by Ohloh, now called Black Duck Open Hub, a site that “aims to index the open-source software development community”. The data was sourced the data from a summary on StackExchange.

Linus Torvalds began developing git in 2005 to manage the source code for the Linux kernel as a replacement for BitKeeper after a messy situation with BitMover, the parent company behind BitKeeper. The key features that have made git successful are it’s distributed nature (history is mirrored on every user’s computer, instead of only being hosted remotely), it’s speed, and the simplicity of its architecture. GitHub, the hosting service for git repositories, launched in 2008, further paving the way for git to become by far the most popular version control system today. According to the 2021 Stack Overflow heDeveloper Survey, git is used by 93% of developers.

The Ohloh data at first appears to illustrate that git took a long time to overtake Subversion (note that the graph starts at 2009 while git was first released in 2005, so there’s really four years missing to the left that we simply don’t have data for). But it’s important to note Ohloh is measuring the total number of repositories using git, whereas the other surveys are measuring which software users report that they’re actually using for their work. In other words, Ohloh is tracking every project that has ever been created in a version control system, when we actually want to track which system is being used more often.

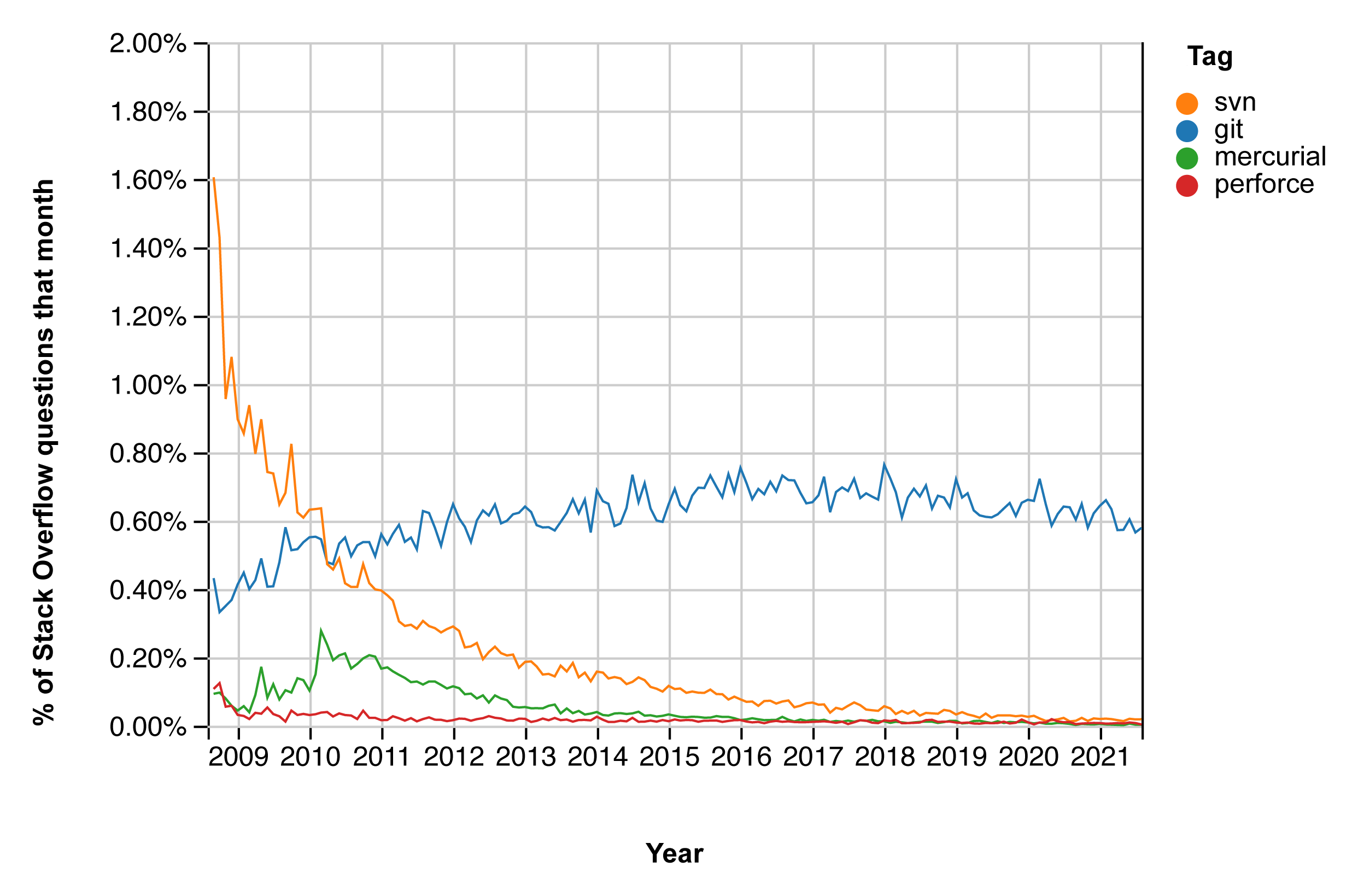

Tracking the number of Stack Overflow questions about different version control systems over time probably maps more closely to which version control system is actually being used. This data shows git overtaking Subversion in 2010, five years after git was first released.

Stack Overflow Trends changes in questions about version control systems over time.

-

These apps often Follow Zawinski’s Law at least in spirit, if not literally. ↩︎

-

Adobe also acquired FreeHand from this transaction, but the FTC blocked Adobe from owning FreeHand, so it’s assets were returned to Altsys (who had been licensing the rights to FreeHand to Aldus). Altsys was acquired by Macromedia in 1995, and it became Macromedia FreeHand. Then of course in 2005, Adobe acquired Macromedia and FreeHand along with it, and it became Adobe FreeHand, which was then discontinued in 2007 due to too much overlap in functionality with Adobe Illustrator. ↩︎

-

The year Sketch was released, 2010, was a year before Apple introduced sandboxing to the Mac App Store. I’ve always thought Sketch was the epitome of what Apple, and the NeXT lineage that preceded it, were trying to accomplish by providing a robust software development framework design to increase developer productivity in order to enhance innovation.

The first web browser, and the genre-defining video games Doom and Quake were both developed on NeXT machiens. Not bad for a platform that only shipped 50,000 units!

Mac App Store sandboxing was the end of that vision, since seemingly no major creative apps can be sandboxed. ↩︎

-

Sketch left the App Store in 2015. ↩︎

-

Development frameworks for user-interface design themselves maturing was another factor that reduced the dependency on exported assets. For example, CSS introduced features like drop shadow and rounded corners around the same time that Sketch was becoming popular. Before those features were added to CSS, implementing those features required exporting assets. ↩︎

-

I’m deliberately excluding Electron when I say no startups have followed in Figma’s footsteps, for a couple of reasons:

- Electron apps don’t leverage the collaborative advantages of the web.

- Electron apps have nothing to do with the 2D WebGL rendering engine that’s at the heart of Figma. This is what allowed Figma to be able to compete in new categories in software that were previously not feasible for web software, e .g., vector and bitmap rendering in this case.

-

Light Table was an important predecessor to Atom, that was an even earlier demonstration of the advantages of a web-based text editor focused on extensions. Again, this early competition illustrates the “primordial ooze” phase of early competition new categories go through (or more precisely in this case, a new way of approaching an old category: text editors). ↩︎

-

One of the great beauties of programming (and writing) is that it’s built on plain text, which removes many of barriers making it difficult to switch software. If the rest of your video editing crew is using Adobe Premiere, there’s no feasible way for you constribute to the same project using something else. Or if you need to export a PDF with exact Pantone color values for a large print run, you’re going to be more hesitant about trying a new application (because even slight deviations could have irrepairable consequences).

Working in plain text has none of these problems, you can freely collaborate with anyone else regardless of what software they’re using, and exporting plain text is always 100% accurate. ↩︎

-

An interesting side note about print design pipelines is that I’ve heard that it’s the reason AppleScript has survived for so long. In particular, the reason AppleScript survived the transition from Mac OS 9 to OS X is that the print design industry depended on it so much. ↩︎

-

Another reason transitions are so rare, is that to clearly trace a transition, you first need to have a single dominant application to transition from. For some reason, single dominant applications seem to be common in visual design fields.

3D modeling, NLEs, and DAWs all have much more diverse markets, so much so that you wouldn’t even be able to talk about a transition, instead you’d just be talking about a new application being added to the cornucopia of options (Ableton Live is a great example of this).

In one of our sections, the Rise of Visual Studio Code is actually about the end of that kind of diversity for text editors (before VS Code, no single text editor had over 30% market share, now in the most recent Stack Overflow Developer Survey VS Code has almost %75), which is astonishing and I’m surprised that it isn’t talked about more. I’d generally consider diversity a healthier market: It provides options for people who want a different experience, the competition forces innovation, and there’s no one product that can exploit it’s market position in user hostile ways. ↩︎

-

I decided to use Bresnahan and Greenstein as a source because the paper is thorough and backed by data, but the paper is looking at mainframe vs. client-server in the context of companies, which is likely the wrong prism to evaluate the transition by. E.g., the New York Times had an article in 1984 stating that personal computers were already outselling mainframes:

For the first time, the value of desktop, personal computers sold in the United States - computers that were almost unheard of only eight years ago - will overtake sales of the large “mainframe” machines that first cast America as the leader in computer technology.

-

The mainframe is also a great example of another consistent pattern: Technology that loses its market dominance rarely fades away completely, it often thrives indefinitely in a niche. The mainframe is a classic example of this, and continues to thrive to this day. In 1991, technology writer Stewart Alsop wrote, “I predict that the last mainframe will be unplugged on 15 March 1996.” Admitting he was wrong, he ate his words in 2002. The mainframe business has only grown since then, for example, here’s how Benedict Evans summarizes post-PC IBM:

The funny thing is, though, that mainframes didn’t go away. IBM went through a near-death experience in the 1990s, but mainframes carried on being used for mainframe things and IBM remained a big tech company. In fact, IBM’s mainframe installed base (measured in MIPS) has grown to be over ten times larger since 2000. Most people working in Silicon Valley today weren’t even born when mainframes were the centre of the tech industry, but they’re still there, inside the same big companies, doing the same big company things. (This isn’t just about IBM either - the UK’s sales tax system runs on DEC’s VAX. Old tech has a long half-life). Mainframes carried on being a good business a long time after IBM stopped being ‘Big Blue’.

-

This graph uses the data from OneStat.com, TheCounter.com, StatOwl.com, and W3Counter on the Usage share of web browsers. Notably, it isn’t always clear whether the data also includes mobile versions of the browsers, as always making sense of the available data is an imprecise process. ↩︎

-

The first stable version of Chrome to support Mac, Linux, and Windows was Chrome 5, released in 2010. ↩︎