Introducing `rep` & `ren`: A New Approach to Command-Line Find & Replace, and Renaming

This post is about two new command-line utilities: rep and ren. Both are available on GitHub.

How to Use rep

-

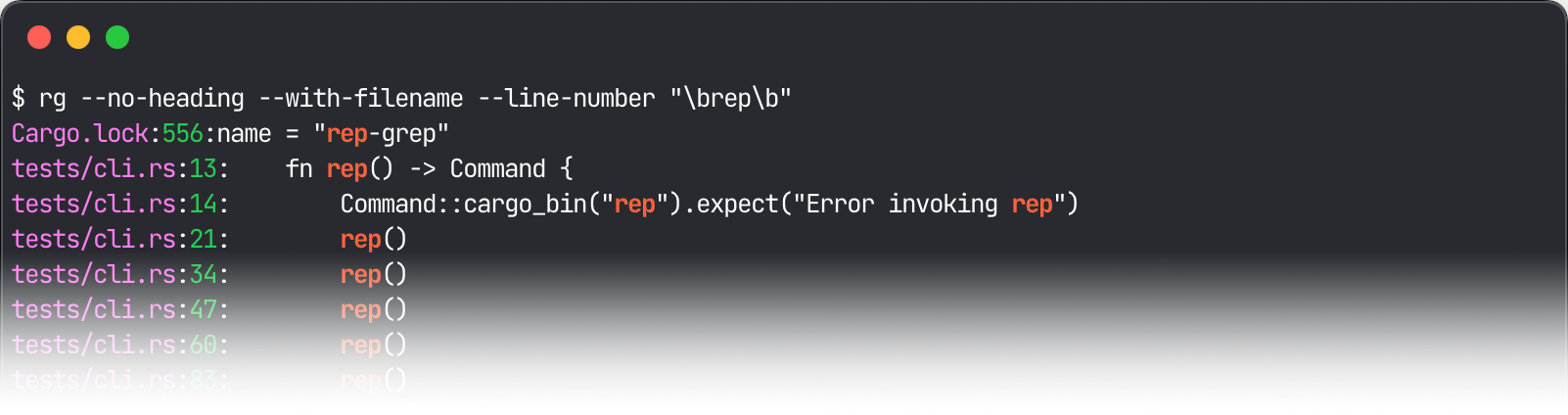

Perform a search with a grep tool like ripgrep:

-

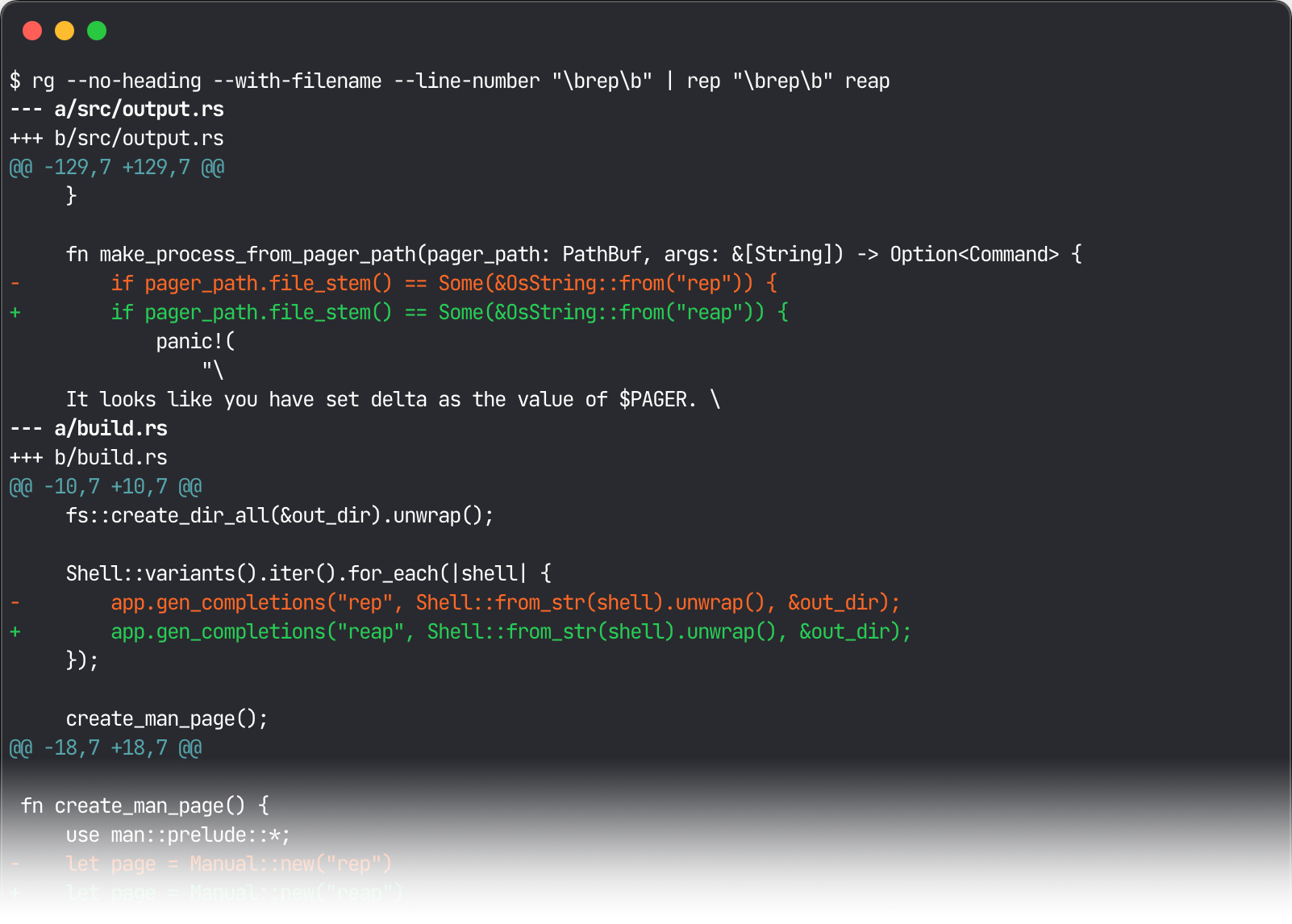

Pipe the results of the search to

rep, and provide search and replace terms as arguments:

-

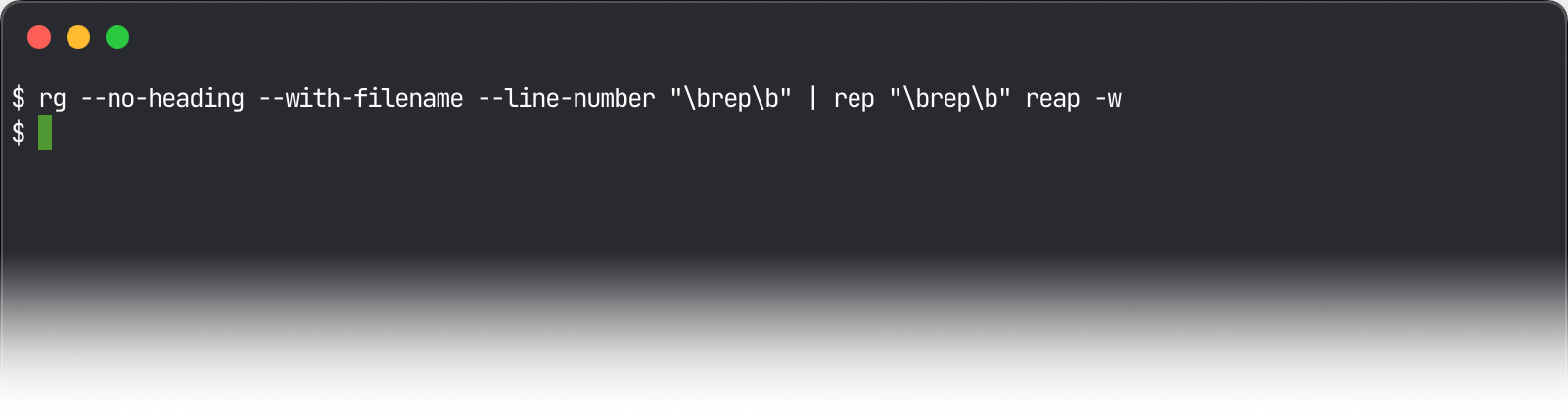

If the diff looks good, pass the

-wflag torepto write the changes to the files:

rep & ren

rep and ren are two new tools for performing find and replace in files, and renaming files, respectively.

They share a similar design in two ways:

- Standard input determines what should be changed.

reptakesgrep-formatted text via standard input to determine which lines to change, andrentakes a single file per line to determine which files to rename. - A preview of the resulting diff is printed to standard output by default. By default,

repandrenboth print a diff of the changes that would result by performing the find and replace or rename. In order to actually write the changes to disk, both have a-w/--writeflag.

Origin Story

Search is what pulled my editing towards the command line1. It began with ack. ack is like grep but it automatically searches recursively and ignores version control directories (e.g., .git/). Just enter ack foo at your shell prompt and see all the results in your project. Today, I use ripgrep, an iteration on the same idea with with a beautifully organized set of command-line flags.

If you do a lot of searching from the command line, eventually you also want to do some editing there. After you’ve performed a search, and you have a list of matches you want to change, what now? For a long time, my answer was to load the matches into the vim quickfix list and use vim built-in support for operating on grep matches to perform the replacement.

Loading matching into an editor and performing the replacement there is a great approach, and it’s ideal for more complex edits2. But there are times when I’d prefer skip the editor altogether. For one, if it’s a quick edit, it’s slower. I’d rather just type out my replacement on the command line without opening my editor3. Then there’s the matter of repeatability: I often do a sequence of several edits, then realize I made a mistake somewhere in the sequence, have to revert the replacement (e.g., with a git checkout .) and start over. If instead I do the edits from the command line, I can just find the replacement in my shell history, fix it there, and quickly re-run the steps in order.

Why not sed?

sed is the definitive search and replace utility for the Unix command line, the problem is, it doesn’t combine well with ripgrep. Here’s the command from an example of a popular answer on Stackoverflow about how you do a recursive find and replace with sed:

find /home/www \( -type d -name .git -prune \) -o -type f -print0 \

| xargs -0 sed -i 's/subdomainA\.example\.com/subdomainB.example.com/g'

You could adapt this to use rg instead of find by using the -l flag which only lists files with matches:

rg "subdomainA\.example\.com" -l -0 \

| xargs -0 sed -i 's/subdomainA\.example\.com/subdomainB.example.com/g'

The problem with this approach is that sed is then performing the search again from scratch on each file, and since sed and rg have different regular expression engines, the matches could be different (or the search could fail with a syntax error)4.

Only performing the replacement on matching lines also makes it easier to write the replacement, because the replacement can then leverage the filtering that’s already been performed by the search. For example, if you were trying to do a find and replacement on function names that end in foo: To find the matching functions, you might including some of the syntax for the function signature (e.g., rg -n 'function .*Foo.*\(' to match all the functions containing Foo), then once you have the matching lines, you can just pipe that to rep Foo Bar (omitting the function signature syntax) to perform the replacement (with sed the replacement would also need to include the function signature, because sed is going to search every line in the file).

These workflow improvements arise because the semantic meaning of the sed command means is to perform a find and replace on the matching files, whereas the rep command means do the replacement on the matching lines.

Another, equally problematic, issue with sed approach is it’s hard to tell what the exactly the result of your find and replace will be. In other words, it’s difficult to interpret the preview what will be done with sed. The sed interface is built around standard streams, as in it takes input either through standard input, or file parameters, and then writes the output directly to standard output, or edits the files in place with a flag. This means that to preview the replacement you’ll just see the raw text of the entire contents of every file that your command will perform a replacement in. Which isn’t practical to parse to understand if the replacement is correct.

rep & ren

rep was written to solve these two problems. Semantically, rep performs the replacement on matching lines, and the replacement is previewed in the form that we’re used to reviewing to determine whether a change is correct: A diff.

ren takes a similar approach but for file renaming. The output of find (or fd) can be piped to ren, so a command looks like this: find *foo* | ren foo bar. ren also displays diff output by default, and writes the changes with -w.

Acknowledgements

- The idea for

repwas inspired bywgrepfor Emacs, which allows editing of agrepresults in a buffer, and writing those changes to the source files. - The structure of the source code, and much of the functionality, was borrowed from

sd,repandrenboth started as forks ofsd. - The code for specifying a custom pager for both

repandrencame from the source code for delta`.

-

Search is all about refinement and the shell excels at refinement. Too many results? Hit the up arrow and make your search more specific. Still too many? Maybe you can just

cdto a subfolder. Want to search across many projects? Justcdup a folder. ↩︎ -

Combining

cdoand:normis a powerful combination to performvimnormal mode commands on each matching line. ↩︎ -

The approach of loading files into a text editor and then using editor functionality to perform the find and replace is both slow because of the number of steps and slow because of the specific implementations of this functionality by the editor. For example,

:cdodoes a bunch of additional work around loading a buffer and setting it up for further editing that’s superfluous to our goal of quickly performing a find and replace. Most engineers don’t share my sensitivity to latency, but for me, who finds great beauty in efficiency, the slowness of using:cdoto perform a find and replace due to all the additional superfluous work it performs, is repugnant. ↩︎ -

Using

rgand withsdinstead ofsedshould resolve most discrepancies between regular expression engines, since they both use the same Rust engine. ↩︎